Today, one might think of the term “women’s bicycle” in a couple of different ways. Casual riders may think of women’s bicycles based primarily on appearance. Although many men also ride drop-frame (step-through) or mixte frame bicycles, at least in the United States, they often are thought of as women’s bikes because they allow the rider to wear a skirt more easily than a diamond-frame bicycle. This understanding of masculine and feminine bicycles dates back a long time.

However, there are also performance bicycles designed with women in mind. Women’s Specific Design (or WSDTM as Trek calls them) are meant to fit average female proportions better than other bicycles. As a side note, there is an inherent problem with thinking of bicycles as “normal” bicycles and women specific bicycle’s, rather than as men specific bicycles and women specific bicycles, but more on that later.

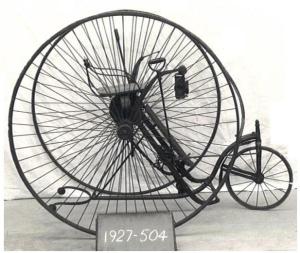

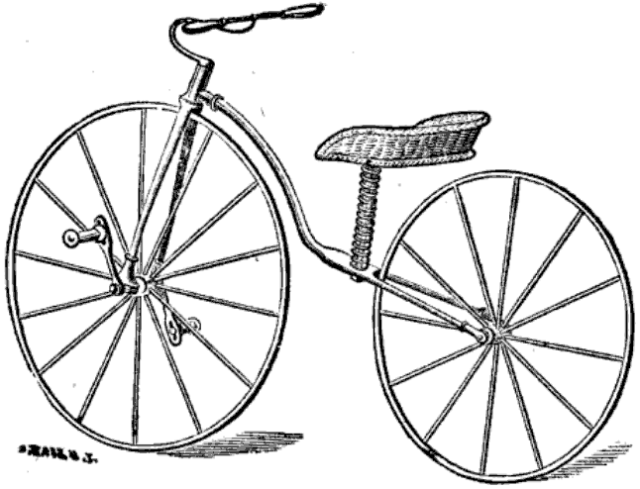

Since the very earliest bicycles- velocipedes- manufacturers have developed bicycles for women. For women who rode velocipedes, there were early drop frames, which allowed for shortened skirts over bloomers. Women’s velocipedes had seats, while men’s had saddles, which had more to do with propriety than a deep understanding of how anatomical differences might affect comfort.

In 1885, the Rover, which some argue is the first modern safety bicycle was introduced at the British bicycle exhibition known as the Stanley Show. In 1887, Dan Albone introduced the first women’s safety bicycle known as the “Anfield Ivel.” The first mass-produced women’s safety bicycle, made the Starley brothers, who also invented the rover, hit the market in 1889.

The first women’s bicycles were designed to accommodate a woman in skirts. Some women did dress in knickerbockers or other modified costumes that allowed them to ride a diamond frame, but it was not the norm. Drop-frame bicycles had disadvantages. They had less structural integrity and thus tended to be heavier than men’s bicycles. Women riding in long skirts were forced to add accessories like heavy chain guards in order to ride safely. Still, specialized women’s bicycles contributed to making bicycling acceptable. They allowed women to wear skirts and also did not force women to straddle a bar, which had sexual connotations. Additionally, their heavier weight made it hard to ride very quickly, which was considered unfeminine.

In a later (post-vacation) entry, I’ll discuss modern women’s bicycles and why there is much more to them than being able to ride them in skirts. Indeed, for performance bicycles, skirts don’t come into the picture at all.